One of the things I love about our clubs are when it leads me to read books that have languished on my shelves for years – and they end up exceeding my expectations. In some cases, by a long way. I’d be surprised if Catherine Carter doesn’t end up on my favourite reads for the year, and I’m grateful to the 1952 Club for getting it off my shelves. (You may have already heard Rachel and me talk about it on Tea or Books?)

I’m also indebted to Jane. Back in 2017, we participated in a Secret Santa at a group devoted to Virago Modern Classics on LibraryThing – and Jane sent me an incredible tower of books. Each of them had a postcard included about why she’d chosen them: ‘This one because I remembered that you liked theatrical settings, because I enjoyed it, and because I remembered that you read PHJ’s book about Ivy Compton-Burnett.’ (And it’s signed!)

Indeed, that’s one of a handful of books I’d previously read by Pamela Hansford Johnson. I enjoyed The Honours Board, I didn’t like An Error of Judgement and I didn’t remember a lot about The Unspeakable Skipton. Well, none of that prepared me for how wonderful Catherine Carter is – and how very different from her other novels.

The books I’ve read by her are always populated by interesting people, but they are treated with authorial detachment. She presents them, she unveils their weaknesses and (less often) their strengths, but she doesn’t seem to have much fondness for them. That’s fine; it’s a type of writing I often enjoy. But Catherine Carter is the opposite – it is suffused by the author’s affection for the main characters, even when they are being weak and flawed. In that way, it reminded me of Elizabeth Goudge. It’s by a long distance my favourite of hers so far.

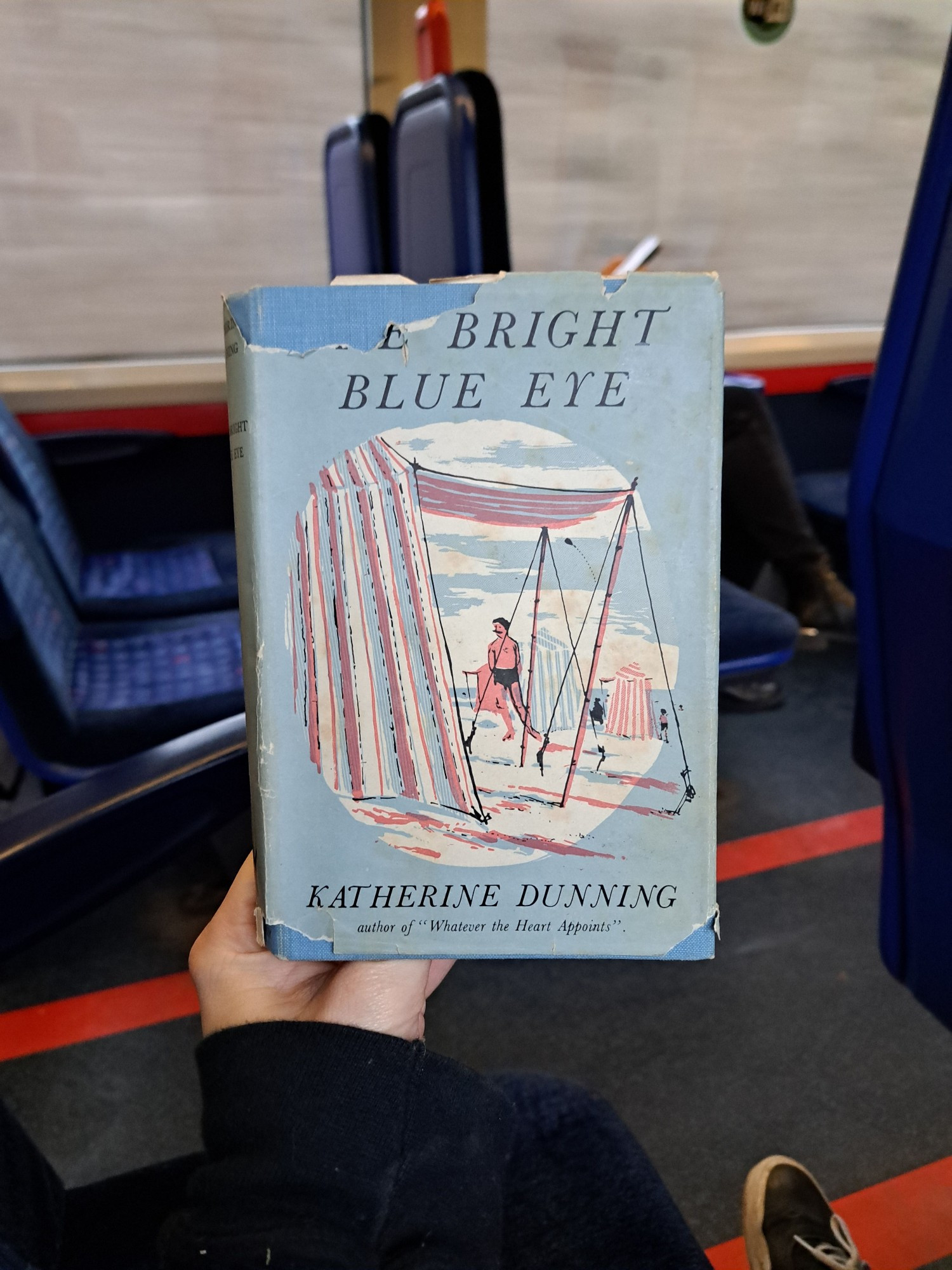

Right, I haven’t told you anything about what Catherine Carter is about – though the cover might give you a clue. Hansford Johnson takes us to the world of 1880s theatre. Specifically the company presided over by Henry Peverel – an actor/manager (but not owner) who is loosely based on Sir Henry Irving in physical appearance and mannerisms, though not story. He is renowned and proud of it. He takes advice from few and has close friendships with even fewer – but he has an abiding love for the theatre, and respect for talent and good judgement, that means he is often unexpectedly amiable. There is nothing malicious about him, but he does consider himself a greater authority than anybody else on what makes a play or a part work. And he is right to think so.

‘In the middle of luncheon,’ goes the opening line, ‘Henry Peverel remembered that he had promised to hear Mostyn’s niece recite.’ And that’s where Catherine Carter comes in. Mostyn is one of Peverel’s almost-friends and a playwright who is respected for his verse plays – but not loved. Peverel doesn’t want to put on one of Mostyn’s plays because he knows it will be a financial disaster – and so, out of a sort of guilt, he hears Catherine Carter recite. She is young, agitated, jumpy. But Peverel sees talent there. He agrees to take her into the company – initially without any parts – but he will coach her once a week.

Catherine Carter is a long book – 467 pages in this edition, though I’ve seen it listed at 576 pages in another. And that means it has plenty of breathing space to take its time. The plot is the gradually evolving relationship between Catherine and Peverel, but Hansford Johnson isn’t rushing anything. We might guess from the outset that they will fall in love, but I was thankful it didn’t happen too suddenly. There is the age gap between them – about 18 years, I think – but it’s really the imbalance of power that would have made any sudden romance hard to stomach. Catherine is an ingenue, albeit one who quickly starts standing up for her own views, challenging those of others around her. Peverel has final say in which roles are given to whom, and even whether or not Catherine is part of the company. It is right that we spend the first hundred or so pages slowly introducing Catherine to this world.

And Hansford Johnson writes so well about the theatre. I don’t know how accurate it is about the specifics of 1880s theatre, but she is wonderful on the process more broadly – the ways in which people explore the psychology of a character, both understanding the motivations as written by the playwright, and finding their own unique interpretations of the role. Hansford Johnson references some (then) modern plays that I think might be made up, though also possible I just don’t know them – but her main focus is on Shakespeare. Along the way, in Catherine Carter, are enveloping explorations of Much Ado About Nothing, Romeo and Juliet, Othello, Hamlet, Anthony and Cleopatra and more. The novel is soaked in a love and respect for theatrical acting, and an unspoken defence of its vitality. How many modern novels would allow an author the time to luxuriate in these discussions? But how brilliantly they build up a sense of this closed world, where theatre and performance are everything.

Here is the moment, after many weeks of their coaching, where Catherine realises she has been elevated from student to equal:

So, as he replied, as they spoke together in a common dream, Catherine became almost wholly Juliet, forgetting herself almost wholly: yet beneath the love and the poetry, and the spell of that perfect metamorphosis which is the rarest but most profound joy which actors know, she realised that she was changed.

Some people become aware at an early stage that the progress of their life and spirit will take place not by a slow imperceptible development but by sudden leaps, so unpredictable that they cannot be watched for. It is the patient people who know this; they are patient because they cannot force what must come to them apparently from without, and through the oddest agencies. They may know, in a second, the determining of twenty years or a lifetime.

When Catherine understood that for the first time Peverel was playing to her as an equal, not reserving part of his mind for the inspection of a pupil, but giving the whole of it to his own interpretation, trusting her to give it to him, unwatched, uninstructed, as freely as he gave to her, she knew that the certainties of her childhood, the affirmations of the looking-glass, had not deceived her. She understood with a calm and radiant clarity, that whether or not she ever became a great actress, it was within her spirit to be so.

Catherine slowly, slowly rises through the ranks of the cast. There is an excellently done section where she is offered her first speaking part in a performance. Flattered by her achievements in these sessions with Peverel, she is holding out for one of the main roles. If not the female lead, then at least a good speaking part. And she is given… the role of the maid. It comes with a handful of words, but that is all. She cannot hide her disappointment – but it is only when overhearing other members of the company being good-naturedly envious that she realises she is wrong. It is a privilege to have any part. But it is too late: Peverel has seen her first reaction. Hansford Johnson is excellent at developing the ways that Catherine and Peverel behave towards each other, and think of each other, throughout the hundreds of pages of Catherine Carter. It is always shifting, evolving. At heart is a mutual respect, but at any moment there might be pity, anger, love, disappointment, care, regret layered over the top. As a portrait of two confident, determined people who are pulled forever into some sort of synergy, it feels positively Shakespearean.

Hansford Johnson’s writing is as rich as her creation of characters. Here is a moment, relatively early in the novel, where Catherine fears she will be cast out:

She could hear the beat of her own heart, echoing from the stony walls. It had not occurred to her before this moment that he might dismiss her, and the idea made her feel sick. All that morning she had thought about him in various differing fashions; humbly, angrily, even contemptuously. Now, her gaze upon his long, lean back, his angular skull, upon the left shoulder borne a little higher than the right, her heart froze in contemplation of a world without him. Echo and emptiness, the fleeting smiles of strangers and the horror of every-day: and his voice taken from her. He must remember that she was young and foolish, and still, still teachable.

Unlocking the door, he held it as she passed before him. He took her not into the office but into his sitting-room, where the fire was lit. The wine with its load of dust blew darkness across the sky. The windowpanes rattled and were rayed with rain. It was a day for farewells.

I thought the pacing of those paragraphs was excellent, particularly the end. And there was something about the repeated ‘still, still teachable’ that I found very effective. Throughout, her writing is beautiful without being unduly showy. I found it a page-turner, despite the slow ease of the plot.

The novel is often also funny – largely due to Catherine’s mother, always called Mrs Carter by the narrative. She is a ‘stage mom’ before the term existed – though one you can’t help loving. Convinced of Catherine’s talent, she sees anything other than a starring role as a bitter insult – while also able to turn any review into a dazzling compliment in her mind. Catherine is constantly embarrassed by her, unsuccessfully trying to repress her, and secure in her love. It’s a well-judged relationship that adds enough humour to the novel to keep it light, without falling into caricature.

Hansford Johnson is also good on the ways in which theatricality can seep into one’s bones. She clearly has a deep respect for it herself, as evidenced by her fascinating delving into the whole process of putting on a play, but she’s not above some gentle teasing of theatrical types. Here are Henry and Catherine, mid-argument:

Henry got up and went to the window. It is a convention of the theatre that persons engaged in any tense or distressful scene are given to walking about; up to the window, down to the desk. And that quarrelling persons are given to conducting their quarrels back to back. It always seemed to Catherine that this was utterly unlike the habits of real life: strong human emotion, in her experience, usually immobilised its subject. For her own part, she had never conducted any business of maximum important to herself whilst moving about a room. Henry, however, a man of the theatre, was playing the scene according to its rules. The stage, Catherine felt, was set; Henry, upstage to window, left; Mrs Carter (seated) centre; herself (seated) downstage, right. She was unhappy and embarrassed.

I realise I’ve hardly told you anything that happens in the novel – but it was really secondary to the feeling of being in it. As Jane noted in her card, I will race towards any novel with a theatrical setting. I’ve never come across one as deeply immersed in theatre as this one, or as successfully. Perhaps it isn’t an authentically 1880s novel, and certainly the dialogue never feels 1880s – nor does it feel 1950s – but that doesn’t matter. Like all the most enjoyable novels, it invites you into a fully realised world, confident in the significance of its characters to keep you entertained and engaged for all of its 476 pages. I’m so glad I accepted the invitation.