There’s a bit of a theme to the two novellas I’ve read in the past two days… or at least their titles.

Day 20: The Year of the Hare (1995) by Arto Paasilinna

Day 20: The Year of the Hare (1995) by Arto Paasilinna

This novella, translated from Finnish by Herbert Lomas, starts with a journalist and a photographer hitting a hare in their care. The journalist (who is called Vatanen, we later learn) gets out to see if it’s ok.

The journalist picked the leveret up and held it in his arms. It was terrified. He snapped off a piece of twig and splinted its hind leg with strips torn from his handkerchief. The hare nestled its head between its little forepaws, ears trembling with the thumping of its heartbeat.

Tired of waiting, the photographer leaves the journalist in the forest – assuming that he’ll catch up to their hotel. But he doesn’t. Instead, he decides to abscond. He doesn’t like his wife anymore, he doesn’t much like his life, and he sees the opportunity to go off wandering through Finland – with the hare.

From here is a quite episodic novella, featuring all kinds of over the top acts – from bear hunting to dangerous fires, threats of pagan sacrifice and more. I’m going to be honest… it all left me a bit cold. The blurb and puff quotes all talk about how funny it is, but I didn’t really understand the wit. I found it all a little drab – big events but very little to make the reader invest in them. Even the hare is curiously characterless. I suppose it’s a sort of deadpan humour that I have enjoyed in other contexts, but for some reason this one didn’t move me.

Day 21: Down the Rabbit Hole (2010) by Juan Pablo Villalobos

Translated from Spanish by Rosalind Harvey, Down the Rabbit Hole comes in around 70 pages – all about a drug gang in Mexico. If I’d known that, I might never have bought it, because I really hate reading about gangs or the Mafia or anything like that. And I’d have missed out on a really brilliant little novella.

It’s told from the perspective of Tochtli, the eight-year-old son of a druglord. This is how it opens…

Some people say say I’m precocious. They say it mainly because they think I know difficult words for a little boy. Some of the difficult words I know are: sordid, disastrous, immaculate, pathetic and devastating. There aren’t really that many people who say I’m precocious. The problem is I don’t know that many people. I know maybe thirteen or fourteen people, and four of them say I’m precocious.

He is indeed pretty precocious, and he does return to those words a lot – particularly sordid and pathetic, which he uses to dismiss a lot of people. (He also uses the f-word a lot, which I rather wish hadn’t been included in this translation.)

Tochtli isn’t shielded from the things happening around them, but he sees them with a child’s incomplete understanding and lack of empathy. He knows that people become corpses at their compound, but is more interested in how many bullets are needed for different parts of the body than thinking about any morality. He is amoral; the people around him are immoral. He is more interested in his various obsessions – Japanese samurai films, a collection of hats, and getting a pygmy hippopotamus from Liberia.

Tochtli’s voice is brilliantly realised in this novella, and Villalobos has created a wholly convincing viewpoint on this horrible world.

his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending.

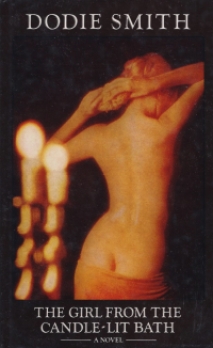

his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending. This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be.

This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be.

Speaking of all things musical, last week I was in London and saw &Juliet – if you get the chance, race to it. It’s the most fun I’ve had a show ever. It might have been custom made for me – it’s a wonderful combination of Shakespeare and 90s/00s pop. The premise is that Anne Hathaway persuades Shakespeare to let Juliet live at the end of Romeo & Juliet – and then what happens next. Set to the music of songwriter Max Martin, who penned hits for people like Backstreet Boys, Britney Spears, Katy Perry, Pink etc. Basically a total nostalgia dream for an older millennial like me, and enough Shakespeare to feel vaguely intellectual. I’m already planning when I’ll go again…

Speaking of all things musical, last week I was in London and saw &Juliet – if you get the chance, race to it. It’s the most fun I’ve had a show ever. It might have been custom made for me – it’s a wonderful combination of Shakespeare and 90s/00s pop. The premise is that Anne Hathaway persuades Shakespeare to let Juliet live at the end of Romeo & Juliet – and then what happens next. Set to the music of songwriter Max Martin, who penned hits for people like Backstreet Boys, Britney Spears, Katy Perry, Pink etc. Basically a total nostalgia dream for an older millennial like me, and enough Shakespeare to feel vaguely intellectual. I’m already planning when I’ll go again… When Brad of

When Brad of ![The Rebecca Notebook and Other Memories by Du Maurier, Daphne [1907-1989]: (1981) | Little Stour Books PBFA Member](https://i0.wp.com/pictures.abebooks.com/inventory/22417507020.jpg?resize=268%2C369&ssl=1) When I was looking at how to double up Novella a Day in May with Ali’s

When I was looking at how to double up Novella a Day in May with Ali’s  Day 10: A Change for the Better (1969) by Susan Hill

Day 10: A Change for the Better (1969) by Susan Hill