Day 28: Sleepless Nights (1979) by Elizabeth Hardwick

Day 28: Sleepless Nights (1979) by Elizabeth Hardwick

Elizabeth Hardwick is one of those authors who has been published both as Virago Modern Classic and a NYRB Classic, and there can few greater accolades (other than being a British Library Women Writers author, am I right??) I bought Sleepless Nights back in 2009, and have a couple other books by Hardwick on my shelf, but have yet to read any.

In this novella, a woman looks back on her life – a jumble of recollections and reflections.

It is June. This is what I have decided to do with my life just now. I will do this work of transformed and even distorted memory and lead this life, the one I am leading now. Every morning the blue clock and the crocheted bedspread with its pink and blue and gray squares and diamonds. How nice it is – this production of a broken old woman in a squalid nursing home. The niceness and the squalor and sorrow in an apathetic battle – that is what I see. More beautiful is the table with the telephone, the books and magazines, the Times at the door, the birdsong of rough, grinding trucks in the street.

That is the opening paragraph, and gives an indication of Hardwick’s striking, rather brilliant prose. And I don’t have a lot to say about Sleepless Nights, because my experience of it was finding her writing absolutely sumptuous and wonderful, and seldom having any idea what was going on. Names would recur, but I was unable to attach much by way of character to them. There is a lovely few pages on Billie Holiday, who is the only name I can remember, a day after reading the novella.

But, nevertheless, I enjoyed reading it. Because each sentence is a little masterpiece. It was like relishing a series of beautiful brushstrokes, but seeing them as abstract mini-artworks, rather than cohering into a single portrait. I daresay that is partly that ‘transformed and even distorted memory’, but mainly because of me. I find I am less and less able to put together a novel told in this abstract way, where beauty is prioritised over clarity. But, as I say, that didn’t stop me enjoying and admiring it. Just probably not quite the way that was intended.

To finish on Hardwick, here’s another quote I noted down:

“Shame is inventive,” Nietzsche said. And that is scarcely the half of it. From shame I have paid attention to clothes, shoes, rings, watches, accents, teeth, points of deportment, turns of speech. The men on the train are wearing clothes which, made for no season, are therefore always unseasonable and contradictory. They are harsh and flimsy, loud and yet lightweight, fashioned with the inappropriateness that is the ruling idea of the year-round. pastels blue as the sea and green as the land; jackets lined with paisley and plaid; seams outlined with wide stitches of another color; revers and pockets outsize; predominance of chilly blue and two-tones; nylon and Dacron in the as-smooth-as-glass finish of the permanently pressed.

Day 29: The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman (2005) by Denis Thériault

Day 29: The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman (2005) by Denis Thériault

What a perfect little novella The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman is. Translated from French by Liedewy Hawke, Thériault’s book is a perfect use of the form – using the slim space to somehow make something with a beauty that depends on delicacy and brevity.

Bilodo is a postman in his late-20s, and perfectly happy. ‘He wouldn’t have wanted to swap places with anyone in the world. Except perhaps with another postman.’ He doesn’t have a girlfriend and doesn’t have many close friends. When he is not delivering letters up and down the many, many steps of the tall buildings on rue des Hêtres, he mostly spends his time in his small apartment, playing videogames and ignoring the attempts of a colleague to find him a girl.

But he does have one illicit pastime:

Among the thousands of soulless pieces of paper he delivered on his rounds, he occasionally came across a personal letter – a less and less common items in this era of email, and all the more fascinating for being so rare. When that happened, Bilodo felt as excited as a prospector spotting a gold nugget in his pan. He did not deliver that letter. Not right away. He took it home and steamed it open. That’s what kept him so busy at night in the privacy of his apartment.

And, one day, one of the envelopes he steams open only includes this:

Under clear water

the newborn baby

swims like a playful otter

He discovers that a woman in Guadalupe, Ségolène, is exchanging haikus with a man on Bilodo’s postal route, Grandpré. Of course, Bilodo can only read Ségolène’s side of the exchange – but he grows obsessed with her, with the haiku form, with this curious relationship that expresses itself solely, and slowly, through the exchange of written verse.

I don’t want to spoil more of the novella, which only comes in at 108 pages, but Bilodo gets much more involved in the correspondence. And the end of The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman is unexpected, brilliant, and curiously beautiful. I gasped, and yet it is the sort of denouement that confirms the beauty of what has gone before.

This is the second novella I’ve read this May about someone discovering a stranger’s personality through their verse, and I think does it more subtly. I’m so impressed by Hawke’s ability to translate the Haikus in a way that, I assume, keeps both their original meaning and the feel. Because the feel is the most important part. And the feel of the whole novella is lovely – precise, delicate, poignant.

Look, yes, I’m cheating again – The Home (1971) isn’t a novella, since it’s 230 pages, but I had a bit more time to read today, and I thought I’d spend it here. And I’m so glad I did – The Home is brilliant (and, indeed, rather better IMO than the other Mortimer I read earlier in May, My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof).

Look, yes, I’m cheating again – The Home (1971) isn’t a novella, since it’s 230 pages, but I had a bit more time to read today, and I thought I’d spend it here. And I’m so glad I did – The Home is brilliant (and, indeed, rather better IMO than the other Mortimer I read earlier in May, My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof). his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending.

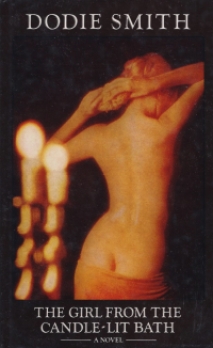

his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending. This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be.

This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be. Oops, I keep cheating on this novella challenge – though today’s cheating was accidental, since I was about 30 pages into Journey Through A Small Planet (1972) by Emanuel Litvinoff when I realised it was an autobiography. Simply from seeing it on the shelf, I had assumed it was a sci-fi novella – though that in itself would have been a surprise, being worlds away from

Oops, I keep cheating on this novella challenge – though today’s cheating was accidental, since I was about 30 pages into Journey Through A Small Planet (1972) by Emanuel Litvinoff when I realised it was an autobiography. Simply from seeing it on the shelf, I had assumed it was a sci-fi novella – though that in itself would have been a surprise, being worlds away from

Blaming was Elizabeth Taylor’s final novel, written while she knew she was dying – and death and mourning are very much at the heart of the book. It opens with Amy and Nick on a cruise. It is to celebrate Nick’s recovery after months of illness, and the first chapter or so is what you might expect of a Taylor novel set at sea – acute observations, gentle interactions, characters reflecting on their own lives as they go about the minutiae of each day.

Blaming was Elizabeth Taylor’s final novel, written while she knew she was dying – and death and mourning are very much at the heart of the book. It opens with Amy and Nick on a cruise. It is to celebrate Nick’s recovery after months of illness, and the first chapter or so is what you might expect of a Taylor novel set at sea – acute observations, gentle interactions, characters reflecting on their own lives as they go about the minutiae of each day.

Sheila Redden has come to France to celebrate her anniversary with Kevin, the doctor of the title. She has come ahead of him, as he has been caught up with work – and they’ve returned to the place where they had their honeymoon fifteen years earlier. Before heading to the very same hotel in Villefranche, she is spending a short time in Paris, visiting an old friend and her current boyfriend. Her life is painfully ordinary. She loves her teenage son Danny, though not all-encompassingly. She supposes herself to love her husband and her life, because that is what one does. Sheila is an introspective woman who manages to avoid looking too close.

Sheila Redden has come to France to celebrate her anniversary with Kevin, the doctor of the title. She has come ahead of him, as he has been caught up with work – and they’ve returned to the place where they had their honeymoon fifteen years earlier. Before heading to the very same hotel in Villefranche, she is spending a short time in Paris, visiting an old friend and her current boyfriend. Her life is painfully ordinary. She loves her teenage son Danny, though not all-encompassingly. She supposes herself to love her husband and her life, because that is what one does. Sheila is an introspective woman who manages to avoid looking too close.