Well, here we are! For the third? fourth? year in a row, I’ve finished a book a day in May. I’ll get onto some thoughts about this year’s experience in a moment, but let’s rattle through the final three books…

24 for 3 (2007) by Jennie Walker

This novella is strong competition for ‘review book that sat on my shelves for the longest period’, as Bloomsbury sent it to me in 2008. It was independently published by the author the year before, so I’m considering it a 2007 title. And the author is in fact poet Charles Boyle – ‘Jennie Walker’ is a pseudonym he has used only once, so far.

24 for 3 is from the perspective of a middle-aged woman and her musings over the course of a week – mostly about her stepson, her husband, and the man she is having an affair with (whom she refers to as ‘the loss-adjustor’). As the title suggests to those in know, this is also a novella about cricket. But her husband and the loss-adjustor are cricket fanatics, and some matches between England and India recur through the week.

What’s the equivalent of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl for a middle-aged man who wants a woman to have an affair with him AND ask him the rules of cricket? It did feel a bit wish-fulfilment at times, and when you know the author is a man, perhaps even less convincing as a real person.

Having said that, it is a rather beautifully written novella – a lovely observant voice, calmly exposing all sorts of truths about human nature. I marked out one paragraph, which is really more about the stepson.

Then his stepmother apologises for speaking to him the way she did and this is sad, almost as sad as the way his parents spend years of their lives fussing about his table manners or whether he’s cleaned his teeth or his toenails need cutting or he’s getting enough vitamin A or B or Q and then suddenly they stop, they ignore him completely, as if the whole family thing has just been a game to pass the time, like throwing balled-up socks. Although after they’ve dropped out oft he game they still insist, when they bother to notice that he’s still around, that the rules apply to him, and that his vitamn levels are the most important things in his life.

I did find the cricket sections more tiresome, as I find pretty much anything about sport in any context. But otherwise it was a really good little book, and it’s a shame there aren’t any more novellas under Walker’s name. Better late than never?

Everything’s Too Something! (1966) by Virginia Graham

This is a collection of short humorous essays collected from Homes and Garden, of all places. I love Graham’s writing, and I want to review this collection properly – rather than in a speedy A Book A Day in May fashion – so watch this space. She deserves to be better known, and I think she might have been if she’d written this sort of thing thirty years earlier. To tide you over, here’s a paragraph that gives a sense of her tone (and probably, on reflection, couldn’t have been written in the 1930s):

Individualists naturally ahve this tendency to think that laws are not made for them, but in a crowded world, and certainly in this sardine tin of an island, it is difificult to be illegal without inconveniencing somebody else. Contemporary youth, of course, asserts its freedom from conventionality by hitting people over the head with milk bottles, and this causes no little inconvenience too; but even the nonconformists who do not go as far as breaking the law often break the code of good manners by which we painstakingly live with each other.

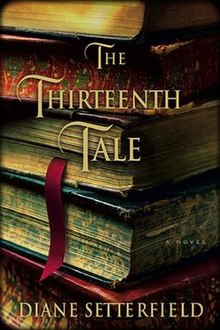

The Thirteenth Tale (2006) by Diane Setterfield

Everybody was reading this when I started blogging and look, only the best part of 20 years later, I’ve listened to the audiobook!

The premise is fun. Vida Winter is the most famous writer in the UK and famously secretive about her life. Whenever she’s been asked about her history, she’s made up one after another fanciful tales. It’s become part of her lore. But, out of the blue, she writes to Margaret Lea requesting – well, more or less demanding – that Margaret write her biography. So off Margaret goes to Vida Winter’s mansion, kept in residence and regularly taken into Vida’s past with long accounts of her childhood, told by Setterfield as a separate narrative. Margaret is your classic heroine of any book like this: bookishly obsessed with the Brontes, feisty when needed, introspective and clever.

The title of the book, incidentally, comes from a collection of Vida Winter’s stories called Thirteen Tales of Change and Desperation, which only has 12 stories in it. What happened to the thirteenth tale?

I enjoyed the book, and Setterfield is definitely an excellent and involving storyteller. I’m always a bit dubious of narratives-within-narratives but it captivated me more than I thought it would. It wasn’t always immediately obvious (in the audiobook) whether we were in present-day with Margaret as ‘I’ or in the distant past with Vida as ‘I’. Perhaps it is marked out more obviously in the print edition?

I think the narrative-within-narrative device was stretched a bit far when it turns into somebody’s rediscovered diary late in the book, but perhaps Setterfield was harkening to her gothic antecedents. Anyway, it was a fun and diverting novel. I wouldn’t necessarily race to read another by her, but I’m glad I finally read The Thirteenth Tale.